|

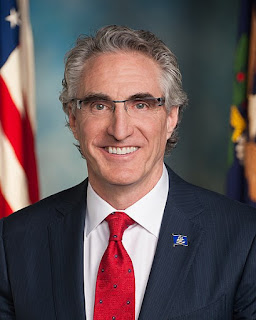

| Donald Trump, White House photo |

My former professor, Charles Urban Larson, a noted authority on persuasive

communication, explains that persuaders can use a unifying style or a pragmatic

style. The unifying style tries to unite us, while the pragmatic (or polarizing) style polarizes the audience.

In an extemporaneous briefing before the Marine One helicopter departure for Cape Kennedy yesterday, Trump said, "MAGA loves black

people." He spoke in a

warm, welcoming, inclusive style, making loving, generous comments

that aggravated the nation’s divisions. That is, his style was unifying, but

his content was harsh, divisive, and racial. Kind and hateful. Uniting and

divisive. Generous words placing a thin cover over hostile thoughts.

Let’s look at how it happened, why it worked rhetorically, and how Trump twisted rhetorical kindness to his own dubious purposes. In an act of what was either supreme tone-deafness or astute political divisiveness, he excluded African Americans at the same time he welcomed them.

“MAGA,” a Trump campaign slogan that has festooned countless homemade signs and red caps, means “Make

America Great Again.” Some of us wonder whether it really means “Make

America White Again,” which would transform the acronym to “MAWA.” Doesn’t have the

same ring, does it? Of course, conservatives piously deny that MAGA carries racist

overtones. Until yesterday, they could say that with a straight face.

What Trump Said

With thousands of people rallying against police violence all over the country, sometimes violently, here’s

what a reporter asked President Trump yesterday at the Marine One departure

briefing:

"Q Mr. President, are you — with your tweets today, are you concerned that you might be stoking more racial violence or more racial discord"

And here is how the President responded:

“Not at all. MAGA says ‘Make America Great Again.’ These are people that love our country. I have no idea if they’re going to be here. I was just asking. But I have no idea if they’re going to be here. But MAGA is ‘Make America Great Again.’ By the way, they love African American people. They love black people. MAGA loves black people.

“I heard that MAGA wanted to be there; a lot of MAGA was going to be there. I have no idea if that’s true or not. But they love our country. Remember that: MAGA is just an expression, but MAGA loves our country.”

Here’s Trump's Positive Message

Trump's surface message was positive and welcoming, after all, “By the way, they love African American people. They love black

people. MAGA loves black people.” That sounds positive because to love people is such a good thing.

So, isn’t that wonderful? “They love African-American people,” said Trump. It is so good to love people. Trump continued in a positive tone: “they love black

people. MAGA loves black people.”

Related Link: Trump's Unifying Speech in South Korea

Well, again, yes, it’s great to love people. How, a Trump supporter could ask, can you call the President and his supporters racists when they love Black people so much? But…

Alas, Here Are Trump’s Divisive Undertones

ProPublica reporter Jessica Huseman explained what was wrong with Trump’s attitude in one quick tweet: “‘MAGA loves black people’ suggests black people aren’t a part of ‘MAGA.’ That they are outside of it. And that’s the point.”

To me, making America great should mean making all of America great. But, since I suspect that there are people who think that no diverse nation can be a great nation, we hear an undertone that making America great means undoing an African American’s presidency and restoring racial boundaries.

What else? Trump also said, “I heard that MAGA wanted to be there; a lot of MAGA was going to be

there." So, to Trump, there were people who protested police brutality, and there was MAGA, and "a lot of MAGA" was going to show up. Again, two distinct groups.

So, what Trump's quick statement told us – between the lines – is that the

people who Make America Great love Black people, but that MAGA supporters and Black

people form two different communities. Political psychologist Bethany Albertson offers a theory that helps us understand this. She talks

about what she calls “multivocal communication.” This is communication that uses the same words to send different messages to different audiences, thus multivocal. We hear a surface meaning,

which, in this case, is that Trump and his supporters love Black people. But people who are tuned

in will hear the underlying message that Black people do not belong

to the MAGA crowd. I assure you, dear readers, that no one, and I mean no one, tunes

into multivocal meanings more attentively than the typical Trump supporter. If liberals didn't get the message, most Republicans caught Trump's drift right away.

The way the United States' political situation is structured, a candidate can win reelection by taking just over 50% of the vote. In fact, the Electoral College system lets a candidate win, as Trump did in 2016, with slightly less than 50%. But if governance requires consent of the governed, what happens when a leader excludes huge chunks of the population from consideration? That can only lead to bedlam, which is, of course, what is happening on the streets today.

Trump's multivocal comment accomplished two purposes. He pretended, for just a moment, to support

racial harmony. He also set up a racial divide. Tricky, isn’t it? It’s

awkward for liberals to complain that Trump and his supporters

love Black people. It is, however, unlikely that his supporters will overlook that he

endorses them over Black people. Some voters are equal, George Orwell might

have said, but some are more equal than others.